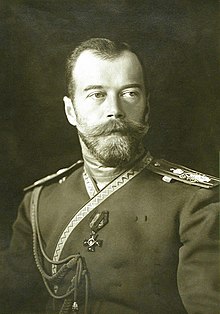

Nicholas II of Russia

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov (18 May 1868 (Old Style) – 17 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer, was the last Tsar of Russia, ruling from 1 November 1894 until his forced abdication on 15 March 1917. His reign saw the fall of the Russian Empire due to the Russian revolution. The Russian Imperial Romanov family (Emperor Nicholas II, his wife Empress Alexandra and their five children: Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia, and Alexei) were shot and bayoneted to death by Bolshevik revolutionaries under Yakov Yurovsky in Yekaterinburg on the night of 16–17 July 1918. Also killed that night were retainers who had accompanied them: notably Eugene Botkin, Anna Demidova, Alexei Trupp and Ivan Kharitonov. The bodies were taken to the Koptyaki forest, where they were stripped and mutilated. Nikolai II Alexandrovich and his family are revered by the Russian Orthodox Church as Christian martyrs, and therefore Saints.

Quotes[edit]

1890s[edit]

- I am not prepared to be Tsar. I never wanted to become one. I know nothing of the business of ruling. I even have no idea how to talk to the ministers.

- As quoted in Richard Wortman (1995). Scenarios of Power: From Alexander II to the abdication of Nicholas II. Princeton University Press. pp. 341–. ISBN 0-691-02947-4.

- I will preserve the principle of Autocracy as firmly and unflinchingly as my late father.

- As quoted in [1]

- I shall never, under any circumstances, agree to a representative form of government because I consider it harmful to the people whom God has entrusted to my care.

- As quoted in [2]

1900s[edit]

- Rioting and disturbances in the capitals and in many localities of Our Empire fill Our heart with great and heavy grief. The well-being of the Russian Sovereign is inseparable from the national well-being; the national sorrow is His sorrow.

- Comment on the 1905 Russian Revolution

- Curse the Duma. It’s all Witte’s fault.

- On the reformist statesman Count Sergei Witte, quoted in [3]

- As long as I live, I will never trust that man (Witte) again with the smallest thing. I had quite enough with last year’s experiment. It is still like a nightmare to me.

- 1906, on the constitutional reforms after the 1905 Revolution, As quoted in [4]

- He [Rasputin] is just a good, religious, simple-minded Russian. When in trouble or assailed by doubts, I like to have a talk with him, and I invariably feel at peace with myself afterward.

- On Grigory Rasputin, As quoted in [5]

- I shall not consider the possibility of any resignation.

- As quoted in Robert K. Massie (1 January 2013). Nicholas and Alexandra: The Tragic, Compelling Story of the Last Tsar and his Family. Head of Zeus. pp. 274–. ISBN 978-1-78185-056-5.

1910s[edit]

- I greet you in these significant and troubled times which Russia is experiencing. Germany, and after her Austria, has declared war on Russia. Such an uplifting of patriotic feeling, love for our homes, and devotion to the Throne, which has swept over our land like a hurricane, serves in my eyes, and I think in yours, as a guarantee that our Great Mother Russia will by the help of our Lord God bring the war to a successful conclusion. In this united outburst of affection and readiness for all sacrifices, even that of life itself, I feel the possibility of upholding our strength, and quietly and with confidence look forward to the future.

- Speech given during the Russian entry into World War I, August 8, 1914, quoted in World War I: Great Speeches in History. Greenhaven Press. 5 February 2021. pp. 49–. ISBN 0-7377-1595-2.

- We are not only protecting our honor and our dignity within the limits of our land, but also that of our brother Slavs, who are of one blood and faith with us. At this time I observe with joy that the feeling of unity among the Slavs has been brought into strong prominence throughout all Russia. I believe that you, each and all, in your place can sustain this Heaven-sent trial and that we all, beginning with myself, will fulfill our duty to the end. Great is the God of our Russian land!

- Speech given during the Russian entry into World War I, August 8, 1914, quoted in World War I: Great Speeches in History. Greenhaven Press. 5 February 2021. pp. 49–. ISBN 0-7377-1595-2.

- Is it possible that for twenty-two years I tried to act for the best and that for twenty-two years it was all a mistake?

- Audience with Mikhail Rodzianko (O.S. Jan 7, 1917)

- That fat Rodzianko has again sent me some nonsense to which I will not even reply.

- response to a telegram from Mikhail Rodzianko during the Russian Revolution warning that the authorities were losing control of Petrograd and urging him to appoint a new government

- In the midst of the great struggle against a foreign foe, who has been striving for three years to enslave our country, it has pleased God to lay on Russia a new and painful trial. Newly arisen popular disturbances in the interior imperil the successful continuation of the stubborn fight. The fate of Russia, the honor of our heroic army, the welfare of our people, the entire future of our dear land, call for the prosecution of the conflict, regardless of the sacrifices, to a triumphant end. The cruel foe is making his last effort and the hour is near when our brave army, together with our glorious Allies, will crush him. In these decisive days in the life of Russia, we deem it our duty to do what we can to help our people to draw together and unite all their forces for the speedier attainment of victory. For this reason we, in agreement with the State Duma, think it best to abdicate the throne of the Russian State and to lay down the Supreme Power. Not wishing to be separated from our beloved son, we hand down our inheritance to our brother, Grand Duke Michael Aleksandrovich, and give him our blessing on mounting the throne of the Russian Empire. We enjoin our brother to govern in union and harmony with the representatives of the people on such principles as they shall see fit to establish. He should bind himself to do so by an oath in the name of our beloved country. We call on all faithful sons of the Fatherland to fulfill their sacred obligations to their country by obeying the Tsar at this hour of national distress, and to help him and the representatives of the people to take Russia out of the position in which she finds herself, and to lead her into the path of victory, well-being, and glory. May the Lord God help Russia!

- Abdication Manifesto, March 3, 1917,

Misattributed[edit]

- The year 1916 was cursed; 1917 will surely be better!

Quotes about Nicholas II[edit]

- The road to civil war began in Petrograd, as the Russian capital had been renamed during the war as a sop to national sentiment ('Sankt Peterburg' had too German a ring to it). Nicholas II, a pious, puritanical man of limited intellectual capacity, came to regard ruling Russia as one long test of inner strength. He worked himself hard, as if determined to prove the veracity of his claim that he was 'the crowned worker'. 'I do the work of three men,' he had declared. 'Let everyone learn to do the work of at least two.' Unfortunately the two other jobs he relished doing - rather more, it would appear, than that of Tsar - were those of secretary and gardener. While conditions at the front deteriorated, he doggedly ploughed through routine correspondence, pausing only to sweep the snow from his own paths. His German-born wife, the Empress Alexandra, did not help, having embraced her own caricature version of Orthodoxy and autocracy. 'Ah my Love,' she wrote to him (in English, as in all their correspondence), 'when at last will you thump with your hand upon the table &C scream at [your ministers] when they act wrongly[?] - one does not fear you - &C one must. . . Oh, my Boy, make one tremble before you - to love you is not enough . . . Be Peter the G., John [Ivan] the Terrible, Emp. Paul - crush them all under you - now don't you laugh, naughty one.' It was hopeless. To the last, Nicholas declined to 'bellow at the people left right && centre'.

- Niall Ferguson, The War of the World: Twentieth-Century Conflict and the Descent of the West (2006), p. 142

- On December 16, 1916, the royal couple's charismatic and corrupt holy man Rasputin was murdered by the Tsar's own cousin, Grand Duke Dmitry, aided and abetted by the effete Prince Felix Yusupov and a right-wing politician named V. M. Purishkevich, in the belief that the monk was exerting a malign influence on the Tsar and on Russian foreign policy. But things did not improve. Deserted by his own generals in what amounted to a mutiny in early March 1917, Nicholas agreed to abdicate, complaining bitterly of 'treachery, cowardice and deceit'. Neither he nor his wife ever understood the revolution that was now unfolding. Indeed, Alexandra's comment on its outbreak deserves wider celebrity as one of the great mis-diagnoses of history: 'It's a hooligan movement, young boys & girls running about &c screaming that they have no bread, only to excite - . . . if it were cold they wld. probably stay in doors.'

- Niall Ferguson, The War of the World: Twentieth-Century Conflict and the Descent of the West (2006), pp. 142-143

- The very insecurity of the Revolution encouraged terrorist tactics. In the early hours of July 17, just hours after Lenin had wired a Danish paper that the 'exczar' was 'safe', the Bolshevik commissar Yakov Yurovsky and a makeshift firing squad of twelve assembled the royal family and their remaining servants in the basement of the commandeered house in Ekaterinburg where they were being held and, after minimal preliminaries, shot them at point-blank range. Trotsky had wanted a spectacular show trial, but Lenin decided it would be better 'not [to] leave the Whites a live banner'.* Unfortunately, because the women had large amounts of jewellery concealed in the linings of their clothes, they were all but bullet-proof. One of the executioners was very nearly killed by a ricochet. Contrary to legend, Princess Anastasia did not survive but was finished off with a bayonet. Only the royal spaniel, Joy, was spared. Other relatives of the Tsar were also taken hostage, including the Grand Dukes Nikolai, Georgy, Dmitry, Pavel and Gavril, four of whom were subsequently shot. Violence begat violence. A month after the execution of the Tsar, an assassination attempt that nearly killed Lenin was the cue for an intensification of the revolutionary terror.

- Niall Ferguson, The War of the World: Twentieth-Century Conflict and the Descent of the West (2006), pp. 149-150

- [David Lloyd George] said the Czar only got his deserts—he had ignored the just pleas of the peasants & had shot them down ruthlessly when they came unarmed to him in 1905.

- David Lloyd George's remarks to Frances Stevenson, as recorded in Stevenson's diary (7 February 1935), quoted in Frances Stevenson, Lloyd George: A Diary, ed. A. J. P. Taylor (1971), p. 300

- [On 2 August 1914] I got to Winter Palace Square where an enormous crowd had congregated with flags, banners, ikons, and portraits of the Tsar. The Emperor appeared on the balcony. The entire crowd at once knelt and sang the Russian national anthem. To those thousands of men on their knees at that moment the Tsar was really the autocrat appointed of God, the military, political and religious leader of his people, the absolute master of their bodies and souls. As I was returning to the embassy, my eyes full of this grandiose spectacle, I could not help thinking of that sinister January 22, 1905, on which the working masses of St. Petersburg, led by the priest Gapon and preceded as now by the sacred images, were assembled as they were assembled to-day before the Winter Palace to plead with "their Father, the Tsar"—and pitilessly shot down.

- Maurice Paléologue, An Ambassador's Memoirs, Vol. I (1924), p. 52

- While the bulk of the Russian forces survived intact and Russia stayed in the war, at least nominally, she lost some of her richest and most populous regions. These defeats generated in Russia a great deal of discontent, especially in liberal and conservative circles. The liberals in parliament (Duma) demanded that the government concede to it the power to appoint ministers. The conservatives wanted Tsar Nicholas II to abdicate in favor of a more forceful member of the imperial family. Rumors spread among the troops and the population at large of treason in high places: the empress, German by origin, was accused of betraying military secrets to the enemy. To compound the government’s troubles, the cities experienced serious inflation, while the deterioration of rail transport caused shortages of food and fuel, especially in Petrograd (as Saint Petersburg had been renamed on the outbreak of the war). The combination of bad news from the front, political disaffection, and economic distress in the urban areas (the countryside was quiet, benefiting from higher prices on foodstuffs) created by October 1916 a revolutionary situation.

- Richard Pipes, Communism: A History (2003)